“and empty grows every bed…” John Berryman

Growing up in Louisiana, I would sit by the Mississippi watching river traffic: ships heading to and from the oil and chemical refineries, tug boats manoeuvring linked barges around the river bends, and ferries crossing cars and pedestrians from my hometown Baton Rouge to the west side of the river. When riding the ferry, I watched flotsam swirl in water so brown and thick that one couldn’t see more than a foot deep. Sometimes at the ferry landing, I talked to an old preacher who had walked the length of the Mississippi from its source to its mouth at least twice, on legs so crippled by an accident that he could only walk aided by canes. He stood at the ferry landing beckoning people to be baptized, which I did once, sinking to my knees in the ooze of the riverbank.1

I couldn’t imagine what lay far north of my hometown, but I knew that below us was New Orleans. The river snaked in a “U” around “the Big Easy,” prevented by high earthen levees from washing away the home of Dixieland music, Cajun voodoo, and the French quarter, with its fine restaurants, strip clubs, historic cathedral, and farmer’s market permeated with the smell of garlic. Several times a year we drove past New Orleans, down the river road to corrupt, mean-spirited Plaquemine Parish so that my father could visit an associate. We would return home with sweet, sweet Louisiana oranges, picked from the few groves that remained after much of the parish was devastatingly flooded in 1927. The levee below New Orleans had been intentionally dynamited to save the city from the rampaging river.

When I was six my parents took me to see the movie Show Boat, the third remake of the Jerome Kern & Oscar Hammerstein musical about life on a Mississippi steamboat. As the river and its lore were an integral part of my life, I loved the movie and memorized the music, most especially Ol’ Man River, sung then by William Warfield, but originally made famous by Paul Robeson in the 1936 film version. I was too young to fully understand the laments in the song’s refrain, with its references to racism and slavery.2 But I instinctively understood the rich, slow flow of the song, and its expression that the river was a greater essence than the people that populate its shores and work its course. When the river passes Baton Rouge, it is very deep, and five times wider than the height of the state’s phallic capitol, then the tallest building in Louisiana. By the time the river reaches New Orleans it has carved a depth of twenty-five stories and the currents are so treacherously swift that whatever falls in, including bodies, may not resurface before reaching the Gulf of Mexico. So I grew up drawn to the river and warned against it.

Alec Soth lives at the northern end of the river and is equally drawn by its power, its lore and its physical grandeur as well as the rich legacy of literature that it has inspired. Trekking along the Mississippi, Soth wasn’t interested in the large cities or industries. Few cities, or even small towns, that were originally founded for river commerce still rely on the river for their existence. Most cities have turned their backs to the “Father of Waters” as the Algonquin Indians named it.3 With no interest in creating an economic or socio-political document about the river and its environs, Soth chose the rich imagery in certain poems as models and inspiration for his photographs. “I see poetry,” he wrote, “as the medium most similar to photography…or at least the photography I pursue. Like poetry, photography is rarely successful with narrative. What is essential is the ‘voice’ (or ‘eye’) and the way this voice pieces together fragments to make something tenuously whole and beautiful.”4

A photographer’s challenge is to develop an “eye” or point of view so personal that it becomes his recognizable style. All decisions of craft (camera, film, and photographic paper) are made to enhance that point of view. It is one step harder to sustain that “eye” throughout a project, so that the pictures are related one to the other, and again, a step harder for the pictures to be sequenced in an order that further shapes and enriches the whole. Sleeping by the Mississippi is one of those rare books that accomplishes this. The Mississippi River, or proximity to it, links Soth’s pictures, but like many artists and writers before him, it’s the river’s potential as a metaphor that fueled his imagination. Dreams and dreaming unify his pictures. Dreams, like the river, transport us, promising freedom and the unknown. Soth's photograph of Charles Lindbergh’s boyhood bed in Little Falls, Minnesota is accompanied by a quote by the mature Lindbergh about dreaming with one’s eyes open. Then, throughout the book, Soth strategically includes photographs of beds and mattresses, which are “like Lindbergh’s plane and Huck’s raft…vehicles for dreaming.”5

The coherence of the project places Soth’s book exactly within the tradition of Walker Evans’ American Photographs and Robert Frank’s The Americans, two books that have shaped the history of photography. While there are many differences in the three books, each photographer repeatedly uses certain physical objects symbolically within individual pictures and within the sequence of the pictures. Soth uses beds the same way Evans used cars and artifacts of American popular culture in American Photographs and Frank employed automobiles and American flags in The Americans.

Dreams are, of course, not the only association evoked by the beds, and Soth’s pictures embody the rich multiplicity of possible references. For instance, the hospital bed in Green Island, Iowa might first evoke images of illness, before one would wonder what feverish dreams taunted its occupant. Or, a bed as a site of procreation is implied in the image of Johnny Cash’s boyhood home. Then, for anyone who grew up in Louisiana, the book’s penultimate picture in Venice evokes thoughts of sweat and mosquitoes. Why did someone carry a bed to that spot, so close to the edge of the marsh? Surely it was not for assignations? Surely the need for privacy was not so great that someone would bare themselves to the gnats, ticks and other vermin, including snakes, ever present by the river, just for a few moments of desire?

In the book’s forty-six ruthlessly edited pictures, Soth alludes to illness, procreation, race, crime, learning, art, music, death, religion, redemption, politics, and cheap sex. Anyone who looks beyond the pictures’ visual beauty will notice such details as the photographs of Martin Luther King Jr. taped to a wall in Memphis, where King’s capacity to dream was assassinated. In another photograph, Memphis’s glass pyramid peeks over a distant bridge. The pyramid, built by city fathers with dreams of greatness akin to their Egyptian namesake, now stands rather for failed dreams, as it is abandoned for the functions for which it was designed and built. Also in Memphis, Soth found the young black woman whose profession is unclear, but presumed, as she displays herself in silver lame hot pants lying on a motel bed. Sexuality is projected again in his picture of the almost indistinguishable mother and daughter from Davenport as well as by the Hustler magazine at Sugar’s place. Then there is Herman’s bed in Kenner, just outside New Orleans, with its ‘see-no-evil /hear–no-evil monkeys’ on the floor, and painted nudes under the air conditioner. Are Herman’s dreams this vivid? Is there a parallel between where and what we dream?

Throughout the book, bibles, crosses and pictures of Jesus reveal the bedrock status of religion in towns large and small along the river. In black ink on his tee shirt, a man at Angola prison declares himself to be a “Preacher + Man,” in opposition to the depersonalizing prison numbers one presumes are on the blue work shirt he has shed. The deteriorated condition of a crucified Christ figure in Buena Vista, Iowa, might be read as lapsed faith. And it is hard to imagine when and why the electrical wires were attached to the cross, making this picture a wildly mixed metaphor.

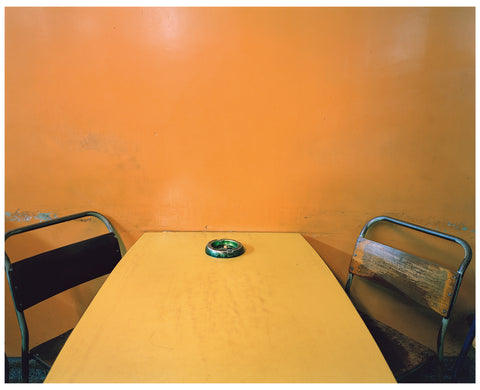

Loneliness is as present as faith throughout the book. The loneliness of travel is endemic in photography’s history for those who leave the studio and travel in search of their subjects. Soth experienced it and recognized it in others. Rather than reject or ignore it, he sought it out, transforming it to empathy. It is all too easy to aim a camera, which can be harsh and unforgiving. When viewing a maquette of Soth’s book, National Public Radio commentator Andrei Codrescu recognized Soth’s piercing “eye” and he wrote to Soth that he had woken his subjects just long enough to reveal “the immemorial, often dreamless, sometimes hopelessly trashy quality of their sleep, then let them sink back into the mud of their impecunious marginality.”6 The judgment and dismissal in Codrescu’s eloquent observation is not really what I sense as Soth’s direction. When working, he is clearly determined, but not confrontational or critical. He evidently has enough charm to gain access to places notoriously closed to the public, such as Angola prison, as well as into people’s homes. An 8 x 10 inch camera on a tripod does not allow for stealth. Unlike street photographers, such as Frank, Lee Friedlander and Garry Winogrand, who carried the quick to operate and easy to conceal 35 mm camera, Soth’s equipment needs to be set up. Then working under a black cloth, Soth must calculate the camera’s settings for exposure and focus. His subjects must be willing to pose and they must be patient. If he is judging them harshly, they don’t sense it or reveal distrust. Instead they proffer cherished objects such as Charles’ model planes and Bonnie’s photograph of an angel. But they aren’t smiling. Soth waits out their self consciousness tendency to smile until they relax back into their thoughts, such as the sad young woman named Kym, who waits alone in a bar booth ironically surrounded by valentine hearts. Crystal, a New Orleans transvestite, poses dressed for church. She’s a big person in a pristine white room, sitting on a spread picturing all the dainty princesses she will never be.

Soth attributes his mid-western upbringing to a sensibility that is more “dark and lonely” than optimistic. He referred me to the poet John Berryman, who leapt to his death from a Mississippi River bridge in January of 1972. Soth particularly noted Berryman’s “Dream Song 1” and its last line, “and empty grows every bed.” Most of the beds in Soth’s pictures are empty, simultaneously evoking all past and future nights as well as past and future occupants, fueling our imagination about their stories and their fates. Often, Soth focuses on the little details other than beds that reveal what mattered to those who live along the river, or what didn’t matter enough to pack when a home was abandoned. There are paintings, such as the portrait in New Orleans. There’s the postcard of a river in the American West, left behind when what must have been more treasured plates and cookie cutters were removed from the wall, leaving the nails and ghostly outlines.

Soth made his first river road venture from Minneapolis to Memphis when he was in college. What was magical on that trip remained vivid and has inspired his recent sojourns, especially the pleasure of watching the land bloom as he moved south. In these pictures, he notes there is also a cultural shift from cold to warm. “Minnesota, Iowa, Wisconsin are like me,” he wrote, “really reserved chilly places. But as you move south, warmth and openness of character develops until finally it is an orgy in the streets of New Orleans.”7

Soth never reveals to us the orgies that he discovered, although a woman named Adelyn appears on Ash Wednesday to have partied hard all through the hours of the preceding “Fat Tuesday,” more commonly known as Mardi Gras. He does convey the increasing luscious vegetation and heavily scented blooms as well as the final great width of the river as it approaches the Gulf. Against the grandeur of the river, he sets the small lives that are caught between sky and earth. The poet Jack Kerouac wrote in the introduction to The Americans that Robert Frank “sucked a sad poem right out of America.” Alec Soth perceives a sad survival. I am drawn again to John Berryman’s “Dream Song I:”

I don’t see how Henry, pried open

for all the world to see, survived.

What he has now to say is a long

Wonder the world can bear & be.8

Soth pries open what he experiences and those whom he met and he wonders (and confirms) that the world can bear & be.

Text by Anne Wilkes Tucker, from 'Sleeping by the Mississippi' by Alec Soth, published September 2017.

1 Robert Frank photographed this old preacher praying by the riverbank in 1955, but I didn’t see that photograph for another 14 years. It became the first art photograph that I owned.

2 “There is an old man called the Mississippi. That’s the old man that I’d like to be. What does he care that the world’s got troubles. What does he care if the land ain’t free?…Ol’ Man River he just keeps rollin along.” Copyright Jerome Kern and Oscar Hammerstein.

3 “Misi” means big and “sipi” means water.

4 Undated letter to Anne Tucker, 2003. Poetry fuels Soth’s imagination and lends shape to his ideas. He has read, and reread poets as diverse as Walt Whitman, Wallace Stevens, John Ashbery, John Berryman and James Wright.

5 Alec Soth’s written answers to questions from curator Karen Irvine, unpublished, 2003.

6 Letter to Alec Soth, 2003.

7 Alec Soth’s written answers to questions from curator Karen Irvine, unpublished, 2003.

8 Copyright John Berryman. The Dream Songs, 1969, Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, Inc.