In my bedroom on the second floor of a two-story house, lost in a sprawl of tract housing overlooking a cul-de-sac in Huntington Beach, California, I had a wall that was collaged all over with cut-outs from fashion magazines, a sort of shrine to supermodels. Paulina, Cindy, Christy and Helena would gaze upon me as I stared at myself in the mirror, wondering when my boobs and legs would start growing, when my skin would clear up and when would I start to look like them. I was coming to the realization that it wasn’t going to happen for me, and I started to resent my reality. I felt ugly.

In my bedroom on the second floor of a two-story house, lost in a sprawl of tract housing overlooking a cul-de-sac in Huntington Beach, California, I had a wall that was collaged all over with cut-outs from fashion magazines, a sort of shrine to supermodels. Paulina, Cindy, Christy and Helena would gaze upon me as I stared at myself in the mirror, wondering when my boobs and legs would start growing, when my skin would clear up and when would I start to look like them. I was coming to the realization that it wasn’t going to happen for me, and I started to resent my reality. I felt ugly. I was taught from movies, television, and especially magazines that a woman’s worth was through her looks, and if I wasn’t going to be tall, I sure as hell better be thin. I starved myself, considering it to be a good day if I only ate one piece of toast. I wrote about my misery and kept track of my “dieting” in my diaries, leaving them open in my drawers, probably with the secret desire that they would be discovered by my mother. If she ever did, she never mentioned it to me. I acted out. I cut myself. My behavior was definitely a signal for my parents to notice something wasn’t right with me. I didn’t know how to talk to them about my feelings. I know they saw the cuts but they never once asked me what was going on.“What she said was sad / But then, all the rejection she’s had / To pretend to be happy / Could only be idiocy”

I was taught from movies, television, and especially magazines that a woman’s worth was through her looks, and if I wasn’t going to be tall, I sure as hell better be thin. I starved myself, considering it to be a good day if I only ate one piece of toast. I wrote about my misery and kept track of my “dieting” in my diaries, leaving them open in my drawers, probably with the secret desire that they would be discovered by my mother. If she ever did, she never mentioned it to me. I acted out. I cut myself. My behavior was definitely a signal for my parents to notice something wasn’t right with me. I didn’t know how to talk to them about my feelings. I know they saw the cuts but they never once asked me what was going on.“What she said was sad / But then, all the rejection she’s had / To pretend to be happy / Could only be idiocy” How perfectly the lyrics to that Smith’s song illustrated my youth. I found my voice in music. I would lock myself in my room and get lost in it. Music spoke for me. I was expressing myself through the songs I blared throughout our house, but I was still ignored by my parents. On weekends they left my brother and I alone to go out drinking, leaving a bit of money on the kitchen counter for food. They didn’t know how to deal with our family issues either. I, along with my problems, was essentially invisible.

How perfectly the lyrics to that Smith’s song illustrated my youth. I found my voice in music. I would lock myself in my room and get lost in it. Music spoke for me. I was expressing myself through the songs I blared throughout our house, but I was still ignored by my parents. On weekends they left my brother and I alone to go out drinking, leaving a bit of money on the kitchen counter for food. They didn’t know how to deal with our family issues either. I, along with my problems, was essentially invisible.

At a certain point, I realized this invisibility equalled freedom, and I started doing whatever I wanted. Fifteen and no curfew. Every night I could, I was hitching rides up to Los Angeles with friends and sometimes strangers, sneaking into concerts, only using my food money for tickets as a last resort. This went on for four years, until I met my first and only boyfriend in 1988. I got on birth control, my face cleared up, and my focus started shifting away from self-criticism and onto more important shit.

At twenty-one, I moved out of my parents’ house. I was engaged to be married and my life was changing fast. All of the mementos from my youth – diaries, love letters, photos, poems, tickets stubs and show flyers – were stuffed into envelopes and boxes and hidden away in a closet, a closed chapter, to be forgotten for over a decade. In a bout of nostalgia one evening, I looked back over my childhood ephemera. I’m not sure why, I probably just wanted a trip down memory lane. As I came across my journals and started to read about what my teenage self had been thinking, the harsh words of self-hatred, the way I saw myself then really struck a chord. It was really interesting for me to reread my thoughts and it made me sad to remember how much pain I was in. It felt like I was reading about someone else. I wished I could go back and hug that person and tell her she’s going to be all right. Other times I would laugh out loud at how dramatic I was. It’s crazy how my feelings were so intense; one wrong word was a matter of life or death to me. I mean, look at the post script on my suicide note: “Can I please have a big funeral with all my friends and stuff, and let everyone know it was a suicide, otherwise this dying was a waste.”

In a bout of nostalgia one evening, I looked back over my childhood ephemera. I’m not sure why, I probably just wanted a trip down memory lane. As I came across my journals and started to read about what my teenage self had been thinking, the harsh words of self-hatred, the way I saw myself then really struck a chord. It was really interesting for me to reread my thoughts and it made me sad to remember how much pain I was in. It felt like I was reading about someone else. I wished I could go back and hug that person and tell her she’s going to be all right. Other times I would laugh out loud at how dramatic I was. It’s crazy how my feelings were so intense; one wrong word was a matter of life or death to me. I mean, look at the post script on my suicide note: “Can I please have a big funeral with all my friends and stuff, and let everyone know it was a suicide, otherwise this dying was a waste.”

I’m in a much better place now than when I first confided in those papers. For me, time and distance have given me a broader perspective on what matters. Over the years I have learned self-acceptance and forgiveness. I think I kept these papers in case I ever had children of my own. If they were feeling down on themselves, I could show them some of my own teenage writings to let them know, “I’ve been there too, and like me, you will get through this.” I never did have children, but I still think sharing my struggles might help others going through something similar. For two decades, I shot portraits of people in the streets with no particular plan for what I would do with the images. Over the last eight years, I came to a striking realization. Many of the women that I approached for portraits had certain qualities in common; I was drawn to these women for a reason. They were either me when I was their age, or what I wished I could have been – beautiful, strong, independent, bad-asses. Once this became apparent, my focus tightened and this project became very clear to me.

For two decades, I shot portraits of people in the streets with no particular plan for what I would do with the images. Over the last eight years, I came to a striking realization. Many of the women that I approached for portraits had certain qualities in common; I was drawn to these women for a reason. They were either me when I was their age, or what I wished I could have been – beautiful, strong, independent, bad-asses. Once this became apparent, my focus tightened and this project became very clear to me.

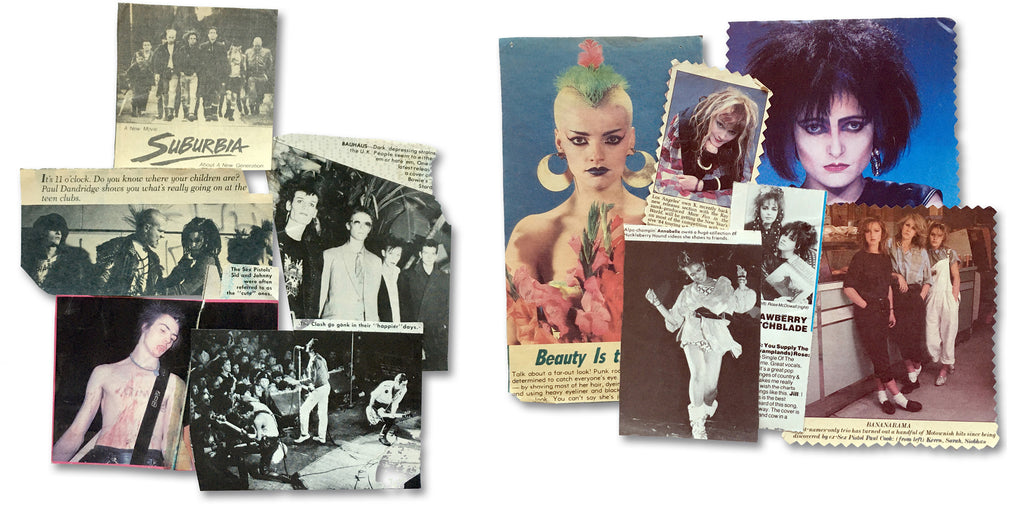

Young girls today are living in a much different world than I did, but the experience of growing up female is universal no matter which era. I see my own struggles, disappointments and bravery in these women. I decided to take these modern portraits and pair them with my own teenage journal entries from 1984 to 1988, along with some of my flyers collected from the shows I went to that reflect the bands I was into during that time. As someone who survived a turbulent transition into adulthood, I hope that this look into my teen-aged mindset and adolescent dramas, paired with these modern girls evolving into adulthood, will convey the sense that there is a light at the end of the tunnel, and we will all be able to look back at our own youth and smile, remembering how intense life feels at that age.

Extract from What She Said by Deanna Templeton, published in January 2021.