The house is quiet. They have gone to bed, leaving me alone, and the electric timer has just switched off the living-room lights. It feels like the house has settled in and finally turned on its side to fall asleep. Years ago I would have gone through my mother's purse for one of her cigarettes and smoked in the dark. It was a magical time that the house was mine.

Tonight, however, I'm restless. I sit at the dining-room table; rummage through the refrigerator. What am I looking for?

All day I’ve been scavenging, poking around in rooms and closets, peering at their things, studying them. I arrange my rolls of exposed film into long rows and count and recount them as if they were loot. There are twenty-eight.

I can hear my mother snoring through the closed bedroom door. Without my asking, she has left a Valium tablet for me. It is sitting on the bathroom counter, next to a full glass of water. I don’t sleep well here. The pillow is too high and spongy, the sheets polyester, the blanket too thin. I wake up in the middle of the night filled with the confusion of motels. This is not my house.

The house where I grew up was sold long ago. Of the three houses that they have lived in since they moved to California from Brooklyn, this one, with its twenty-foot cathedral ceilings and Italian tile floor, is the least alive for me. At the same time, it seems to have a life of its own: the radio turns itself on in the morning with the sprinklers; the lights go on in the evening and turn themselves off at eleven. Everything is under control.

Sitting finally on the couch in the dark living room, I begin to sink. I feel chills moving up my back and along my arms. I become sensitive to night sounds: the stirring of the dog, the refrigerator, a neighbor’s car and automatic garage door, my parents in their bedroom. My body seems to grow smaller, as if it is finally adjusting itself to the age I feel whenever I’m in their house. It’s like I’m releasing the air from an inflatable image and shrinking back down to an essential form. Is this why I’ve come here? To find myself by photographing them?

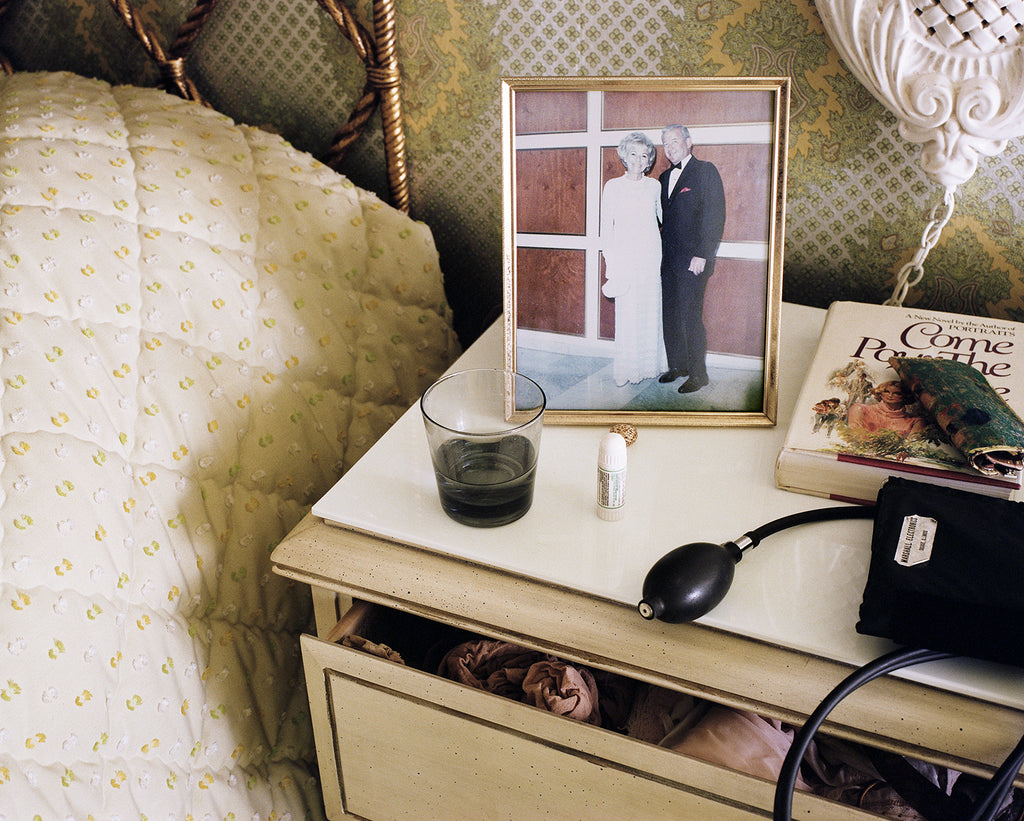

Every few months I visit, loaded down with camera gear and ideas for pictures. It takes a day or two for most of these ideas to seem strained or foolish and then I’m left with cases of unexposed film and a feeling of desperation. I bargain with my father, trading him hours of weeding in his garden for minutes of his time posing for me. When I finally begin to photograph him, I feel so anxious that I retake the same pictures I made years ago. After a few days of this I become so distracted that I miss most of the wonderful, daily things and instead I begin to act like an anthropologist or a cop — photographing shoes, papers, the surfaces of dressers. Evidence. It’s only when I give up trying to make pictures and begin to enjoy the time spent with them that anything of value ever happens.

The other day my father asked me, “What do you do with all those pictures that you make? You must have thousands of them by now.” When he takes pictures, he has the entire roll printed and keeps all of the three-by-five-inch prints in envelopes that one day he plans to put into albums. A few years ago he presented me and my two brothers with scrapbooks filled with pictures that he had made of us over the years. Our snapshot biographies.

I tell him that most of my photographs aren’t very interesting and so I just file the negatives away in boxes.

He can’t believe it. “You shoot thirty rolls of film to get one or two pictures that you like. Doesn’t that worry you?” He has a knack for finding the sore spot.

“No. I love making pictures, even if most of the results are lousy.” The real issue is that many of the pictures that I do like trouble me more than all the ones that are filed away. I worry that they will trouble him as well.

I remember arguing with him over fifteen years ago about a photograph I made of my mother. It was a very simple and direct picture of her standing in front of a sliding glass door holding a cooked turkey on a silver platter. He accused me of creating an image that had less to do with her than with my own stereotypes of how people age. I argued that our conflicting notions about who mom is and how she should be represented are based on our different relationships to her. She is my mother but his wife. I pointed out that in almost every picture of her that he has taken she is posed like a model selling one thing or another.

“Look,” I said, “I don’t see her in that way, I don’t glamorize her with my photographs and that’s why you claim that the pictures undermine her vitality. It’s your image of her vitality that they counter.”

“All I know is that you have some stake in making us look older and more despairing than we really feel,” he answers. “I really don’t know what you are trying to get at.”

Excerpt from Chapter 1 of Pictures From Home by Larry Sultan.

Second printing of the MACK edition

Embossed hardback with tipped-in image front and back

192 pages, 140 colour plates

€60 £50 $65