Blog

In his last three years Johnson made and mailed art incessantly, went out for a drive most days, and ran through about one camera a week. When he finished a twenty-four-frame roll, he would drop off the camera—he used a couple of Kodaks at first and then, consistently, Fujicolor Quicksnaps—at Living Color, a shop in Glen Cove, for developing and printing. After turning sixty-five in October 1992, he often took advantage of a senior discount and ordered duplicate prints.

Coaches use the mental image of the ball going in the hoop as a way of coordinating all of the muscular activity. And if the player has innate ability and has spent so many hours practicing that they have ingrained, muscular understanding, the player can focus on the image and their body will do the rest. Likewise, a photographer who has spent years consciously examining how the world is translated by the camera into a photograph can use a mental image to coordinate all of the myriad decisions that go into organizing a picture.

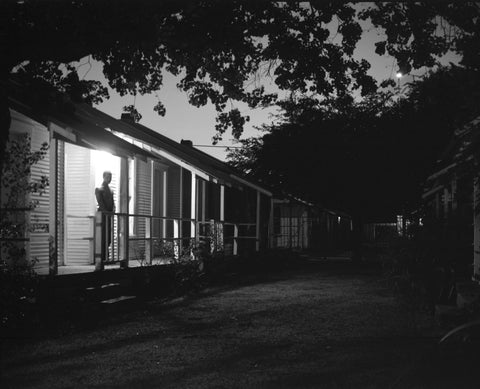

These images are an attempt at maintaining the integrity of the space they have claimed, visceral and existential. They reverberate in varying frequencies of belonging. They set their gaze on the rhythms, vibes, and musical patterns that make up Black life in a certain section of Third Ward. Even though the spaces they inhabit have been broken in, hollowed out, and formed over a number of generations to their Black presence, somewhere there lingers doubt. Our history (for I am a Black man), if we are honest, does not lend itself to a solid belief in “the American franchise.”

break up with your ***friend

he ain’t a nigga.

i’m the nigga you see

when the lights go out

flame sparked spectrum,

We flare at every end.

he ain’t a nigga.

i’m the nigga you see

when the lights go out

flame sparked spectrum,

We flare at every end.